Tarted becoming an issue just as she began stressing about

Introduction As fitness is an extremely diverse sphere, goals vary from person to person. We’re proud to say that our

Introduction As fitness is an extremely diverse sphere, goals vary from person to person. We’re proud to say that our

Shrey had always been interested in fitness and nutrition. Working with a student as dedicated as Shrey is always a

Shrey had always been interested in fitness and nutrition. Working with a student as dedicated as Shrey is always a

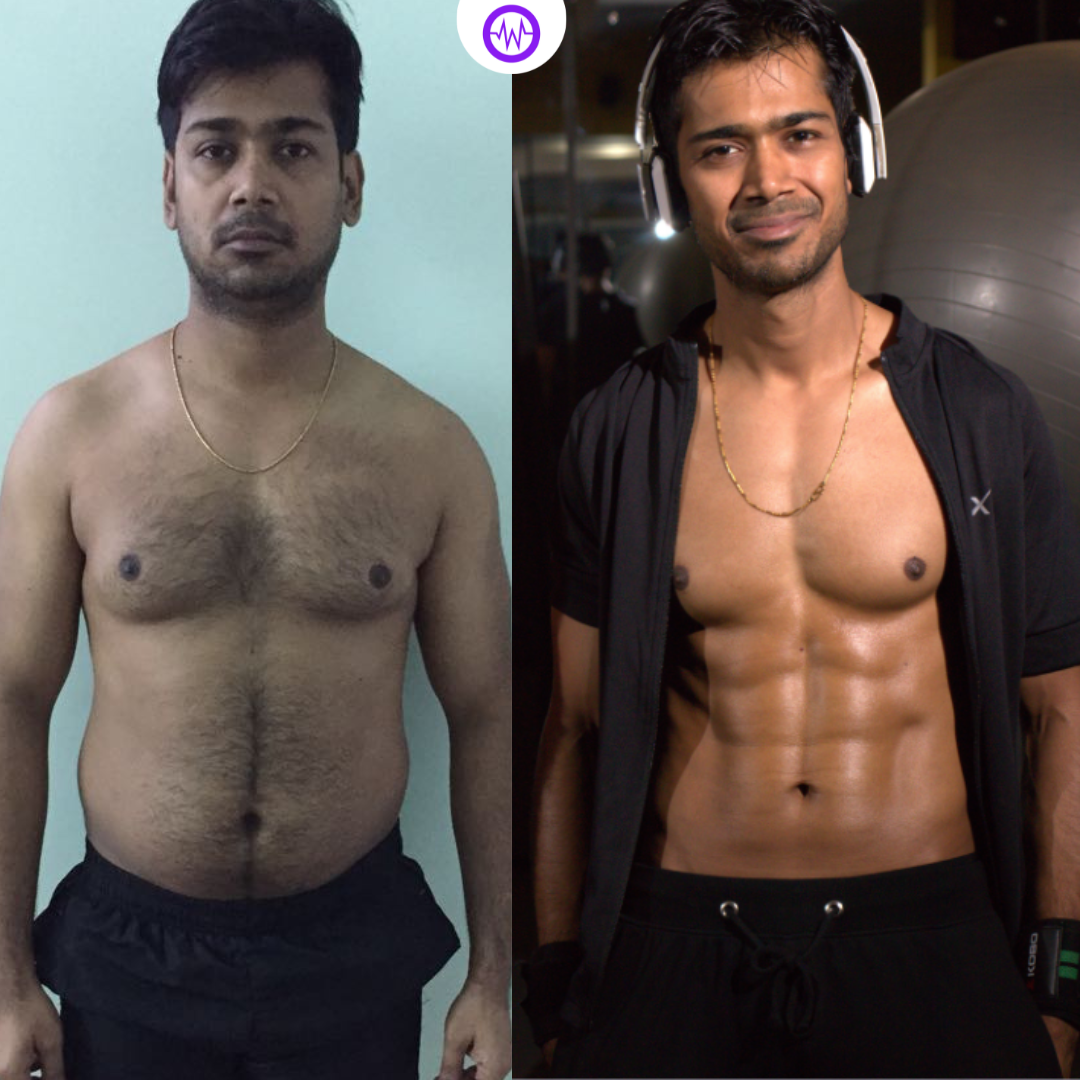

HOW TANAY GOT SHREDDED DOWN TO 12% BODY FAT NAME – TANAY MONDAL OCCUPATION OR PROFESSION – FITNESS COACH START

VEGAN DOCTOR SANDEEP’S 6 MONTH TRANSFORMATION NAME – DR. SANDEEP GUPTAOCCUPATION ~ OPHTHALMOLOGIST (EYE SPECIALIST)START WEIGHT ~ 78KGSGOAL WEIGHT ~

Anoushka is a brilliant classical dancer who performs Odissi dance. Owing to disordered eating habits and personal issues, she ended

Like many, Kusum Melwani struggled to maintain weight due to a poor lifestyle and health issues. She recalls that her

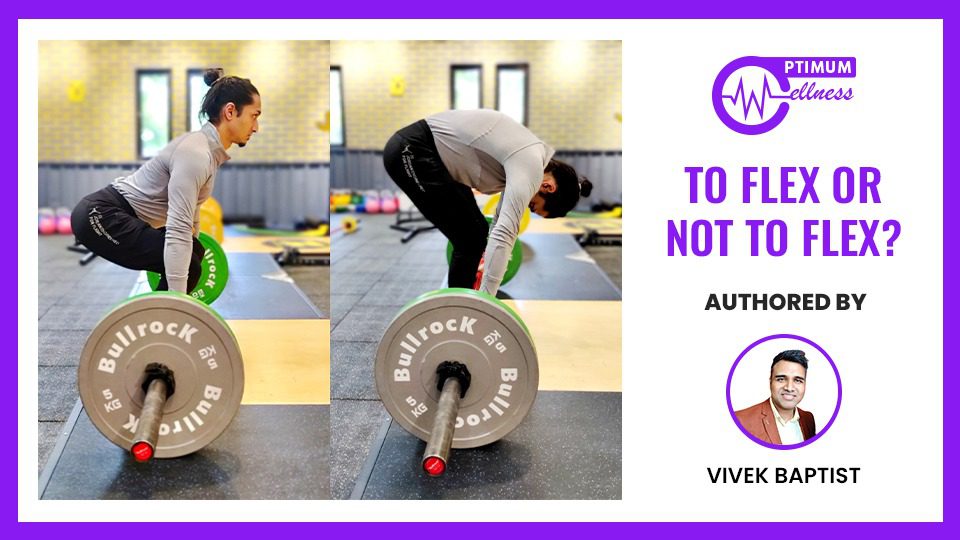

As fitness professionals, most of us have had our share of those odd, unsolicited comments or personal messages from a

Fat loss is probably the most widely sought-after fitness goal. If you’re on your fat loss journey, you might end

Carbs have always been the dietary enemy, especially for those trying to lose weight. But, at the same time, there